Les Miserables

Les Miserables The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame The Man Who Laughs

The Man Who Laughs The Last Day of a Condemned Man

The Last Day of a Condemned Man The Toilers of the Sea

The Toilers of the Sea Waterloo

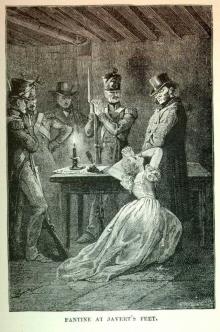

Waterloo Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine

Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius

Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette

Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean

Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)