- Home

- Victor Hugo

The Man Who Laughs Page 2

The Man Who Laughs Read online

Page 2

II

Homo was no ordinary wolf. From his appetite for medlars and potatoes he might have been taken for a prairie wolf; from his dark hide, for a lycaon; and from his howl, prolonged into a bark, for a dog of Chili. But no one has as yet observed the eyeball of a dog of Chili sufficiently to enable us to determine whether he be not a fox; and Homo was a real wolf. He was five feet long, which is a fine length for a wolf, even in Lithuania, he was very strong; he looked at you askance, which was not his fault; he had a soft tongue, with which he occasionally licked Ursus; he had a narrow brush of short bristles on his backbone, and he was lean with the wholesome leanness of a forest life. Before he knew Ursus and had a carriage to draw, he thought nothing of doing his fifty miles a night. Ursus, meeting him in a thicket near a stream of running water, had conceived a high opinion of him from seeing the skill and sagacity with which he fished out crayfish, and welcomed him as an honest and genuine Koupara wolf, of the kind called crab-eater.

As a beast of burden, Ursus preferred Homo to a donkey. He would have felt repugnance to having his hut drawn by an ass; he thought too highly of the ass for that. Moreover, he had observed that the ass, a four-legged thinker, little understood by men, has a habit of cocking his ears uneasily when philosophers talk nonsense. In life the ass is a third person between our thoughts and ourselves, and acts as a restraint. As a friend, Ursus preferred Homo to a dog, considering that the love of a wolf is more rare.

Hence it was that Homo sufficed for Ursus. Homo was for Ursus more than a companion, he was an analogue. Ursus used to pat the wolf's empty ribs, saying: "I have found the second volume of myself!" Again he said, "When I am dead, any one wishing to know me need only study Homo. I shall leave a true copy behind me."

The English law, not very lenient to beasts of the forest, might have picked a quarrel with the wolf, and have put him to trouble for his assurance in going freely about the towns: but Homo took advantage of the immunity granted by a statute of Edward IV to servants: "Every servant in attendance on his master is free to come and go." Besides, a certain relaxation of the law had resulted with regard to wolves, in consequence of its being the fashion of the ladies of the Court, under the later Stuarts, to have, instead of dogs, little wolves, called adives, about the size of cats, which were brought from Asia at great cost.

Ursus had communicated to Homo a portion of his talents: such as to stand upright, to restrain his rage into sulkiness, to growl instead of howling, etc.; and on his part, the wolf had taught the man what he knew--to do without a roof, without bread and fire, to prefer hunger in the woods to slavery in a palace.

The van, hut, and vehicle in one, which traversed so many different roads without, however, leaving Great Britain, had four wheels, with shaft for the wolf and a splinter-bar for the man. The splinter-bar came into use when the roads were bad. The van was strong, although it was built of light boards like a dovecot. In front there was a glass door with a little balcony used for orations, which had something of the character of the platform tempered by an air of the pulpit. At the back there was a door with a practicable panel. By lowering the three steps which turned on a hinge below the door, access was gained to the hut, which at night was securely fastened with bolt and lock. Rain and snow had fallen plentifully on it; it had been painted, but of what colour it was difficult to say, change of season being to vans what changes of reign are to courtiers. In front, outside, was a board--a kind of frontispiece, on which the following inscription might once have been deciphered; it was in black letters on a white ground, but by degrees the characters had become confused and blurred:

"By friction gold loses every year a fourteen-hundredth part of its bulk. This is what is called the Wear. Hence it follows that on fourteen hundred millions of gold in circulation throughout the world, one million is lost annually. This million dissolves into dust, flies away, floats about, is reduced to atoms, charges, drugs, weighs down consciences, amalgamates with the souls of the rich whom it renders proud, and with those of the poor whom it renders brutish."

The inscription, rubbed and blotted by the rain and by kindness of nature, was fortunately illegible, for it is possible that its philosophy concerning the inhalation of gold, at the same time both enigmatical and lucid, might not have been to the taste of the sheriffs, the provost-marshals, and other big-wigs of the law. English legislation did not trifle in those days. It did not take much to make a man a felon. The magistrates were ferocious by tradition, and cruelty was a matter of routine. The judges of assize increased and multiplied. Jefferies had become a breed.

III

In the interior of the van there were two other inscriptions. Above the box, on a whitewashed plank, a hand had written in ink as follows:

THE ONLY THINGS NECESSARY TO KNOW. [1]

"The Baron, peer of England, wears a cap with six pearls. The coronet begins with the rank of Viscount. The Viscount wears a coronet of which the pearls are without number. The Earl a coronet with the pearls upon points, mingled with strawberry leaves placed low between. The Marquis, one with pearls and leaves on the same level. The Duke, one with strawberry leaves alone--no pearls. The Royal Duke, a circlet of crosses and fleurs-de-lis. The Prince of Wales, crown like that of the King, but unclosed.

"The Duke is a most high and most puissant prince, the Marquis and Earl most noble and puissant lord, the Viscount noble and puissant lord, the Baron a trusty lord. The Duke is his Grace; the other Peers their Lordships. Most honourable is higher than right honourable.

"Lords who are peers are lords in their own right. Lords who are not peers are lords by courtesy:--there are no real lords, excepting such as are peers.

"The House of Lords is a chamber and a court, Concilium et Curia, legislature and court of justice. The Commons, who are the people, when ordered to the bar of the Lords, humbly present themselves bareheaded before the peers, who remain covered. The Commons send up their bills by forty members, who present the bill with three low bows. The Lords send their bills to the Commons by a mere clerk. In case of disagreement, the two Houses confer in the Painted Chamber, the Peers seated and covered, the Commons standing and bareheaded.

"Peers go to Parliament in their coaches in file; the Commons do not. Some peers go to Westminster in open four-wheeled chariots. The use of these and of coaches emblazoned with coats-of-arms and coronets is allowed only to peers, and forms a portion of their dignity.

"Barons have the same rank as bishops. To be a baron peer of England, it is necessary to be in possession of a tenure from the king per Baroniam integram, by full barony. The full barony consists of thirteen knights' fees and one-third part, each knight's fee being of the value of 20£ sterling, which makes in all 400 marks. The head of a barony (Caput baroniæ) is a castle disposed by inheritance, as England herself--that is to say, descending to daughters if there be no sons, and in that case going to the eldest daughter, cæteris filiabus aliundè satisfactis. [2]

"Barons have the degree of lord: in Saxon, laford; dominus in high Latin; Lordus in low Latin. The eldest and younger sons of viscounts and barons are the first esquires in the kingdom. The eldest sons of peers take precedence of knights of the garter. The younger sons do not. The eldest son of a viscount comes after all barons, and precedes all baronets. Every daughter of a peer is a Lady. Other English girls are plain Mistress.

"All judges rank below peers. The sergeant wears a lambskin tippet; the judge one of patchwork, de minuto vario, made up of a variety of little white furs, always excepting ermine. Ermine is reserved for peers and the king.

"A lord never takes an oath, either to the crown or the law. His word suffices; he says, Upon my honour.

"By a law of Edward the Sixth, peers have the privilege of committing manslaughter. A peer who kills a man without premeditation is not prosecuted.

"The persons of peers are inviolable.

"A peer can not be held in durance, save in the Tower of London.

"A writ of supplicavit can not be granted aga

inst a peer.

"A peer sent for by the king has the right to kill one or two deer in the royal park.

"A peer holds in his castle a baron's court of justice.

"It is unworthy of a peer to walk the street in a cloak, followed by two footmen. He should only show himself attended by a great train of gentlemen of his household.

"A peer can be amerced only by his peers, and never to any greater amount than five pounds, excepting in the case of a duke, who can be amerced ten.

"A peer may retain six aliens born, any other Englishman but four.

"A peer can have wine custom-free; an earl eight tons.

"A peer is alone exempt from presenting himself before the sheriff of the circuit.

"A peer can not be assessed toward the militia.

"When it pleases a peer he raises a regiment and gives it to the king; thus have done their graces the Dukes of Athol, Hamilton, and Northumberland.

"A peer can hold only of a peer.

"In a civil cause he can demand the adjournment of the case, if there be not at least one knight on the jury.

"A peer nominates his own chaplains. A baron appoints three chaplains; a viscount four; an earl and a marquis five; a duke six.

"A peer can not be put to the rack, even for high treason. A peer can not be branded on the hand. A peer is a clerk, though he knows not how to read. In law he knows.

"A duke has a right to a canopy, or cloth of state, in all places where the king is not present; a viscount may have one in his house; a baron has a cover of assay, which may be held under his cup while he drinks. A baroness has the right to have her train borne by a man in the presence of a viscountess.

"Eighty-six tables, with five hundred dishes, are served every day in the royal palace at each meal. [3]

"If a plebeian strike a lord, his hand is cut off.

"A lord is very nearly a king.

"The king is very nearly a god.

"The earth is a lordship.

"The English address God as my lord!"

Opposite this writing was written a second one, in the same fashion, which ran thus:

SATISFACTION WHICH MUST SUFFICE THOSE WHO HAVE NOTHING

"Henry Auverquerque, Earl of Grantham, who sits in the House of Lords between the Earl of Jersey and the Earl of Greenwich, has a hundred thousand a year. To his lordship belongs the palace of Grantham Terrace, built all of marble and famous for what is called the labyrinth of passages--a curiosity which contains the scarlet corridor in marble of Sarancolin, the brown corridor in lumachel of Astracan, the white corridor in marble of Lani, the black corridor in marble of Alabanda, the gray corridor in marble of Staremma, the yellow corridor in marble of Hesse, the green corridor in marble of the Tyrol, the red corridor, half cherry spotted marble of Bohemia, half lumachel of Cordova, the blue corridor in turquin of Genoa, the violet in granite of Catalonia, the mourning-hued corridor veined black and white in slate of Murviedro, the pink corridor in cipolin of the Alps, the pearl corridor in lumachel of Nonetta, and the corridor of all colours, called the courtiers' corridor, in motley.

"Richard Lowther, Viscount Lonsdale, owns Lowther in Westmoreland, which has a magnificent approach, and a flight of entrance steps which seem to invite the ingress of kings.

"Richard, Earl of Scarborough, Viscount and Baron Lumley of Lumley Castle, Viscount Lumley of Waterford in Ireland, and Lord Lieutenant and Vice-Admiral of the county of Northumberland and of Durham, both city and country, owns the double castleward of old and new Sandbeck, where you admire a superb railing, in the form of a semicircle, surrounding the basin of a matchless fountain. He has, besides, his castle of Lumley.

"Robert Darcy, Earl of Holderness, has his domain of Holderness, with baronial towers, and large gardens laid out in French fashion, where he drives in his coach-and-six, preceded by two outriders, as becomes a peer of England.

"Charles Beauclerc, Duke of St. Albans, Earl of Burford, Baron Hedington, Grand Falconer of England, has an abode at Windsor, regal even by the side of the king's.

"Charles Bodville Robartes, Baron Robartes of Truro, Viscount Bodmin, and Earl of Radnor, owns Wimpole in Cambridgeshire, which is as three palaces in one, having three façades, one bowed and two triangular. The approach is by an avenue of trees four deep.

"The most noble and most puissant Lord Philip, Baron Herbert of Cardiff, Earl of Montgomery and of Pembroke, Ross of Kendall, Parr, Fitzhugh, Marmion, St. Quentin, and Herbert of Shurland, Warden of the Stannaries in the counties of Cornwall and Devon, hereditary visitor of Jesus College, possesses the wonderful gardens at Wilton, where there are two sheaf-like fountains, finer than those of his most Christian Majesty King Louis XIV at Versailles.

"Charles Seymour, Duke of Somerset, owns Somerset House on the Thames, which is equal to the Villa Pamphili at Rome. On the chimney-piece are seen two porcelain vases of the dynasty of the Yuens, which are worth half a million in French money.

"In Yorkshire, Arthur, Lord Ingram, Viscount Ire in, has Temple Newsam, which is entered under a triumphal arch, and which has large wide roofs resembling Moorish terraces.

"Robert, Lord Ferrers of Chartly, Bourchier and Louvaine, has Staunton Harold in Leicestershire, of which the park is geometrically planned in the shape of a temple with a façade, and in front of the piece of water is the great church with the square belfry, which belongs to his lordship.

"In the county of Northampton, Charles Spencer, Earl of Sunderland, member of His Majesty's Privy Council, possesses Althorp, at the entrance of which is a railing with four columns surmounted by groups in marble.

"Laurence Hyde, Earl of Rochester, has, in Surrey, New Park, rendered magnificent by its sculptured pinnacles, its circular lawn belted by trees, and its woodland, at the extremity of which is a little mountain, artistically rounded, and surmounted by a large oak, which can be seen from afar.

"Philip Stanhope, Earl of Chesterfield, possesses Bretby Hall in Derbyshire, with a splendid clock tower, falconries, warrens, and very fine sheets of water, long, square, and oval, one of which is shaped like a mirror, and has two jets, which throw the water to a great height.

"Charles Cornwallis, Baron Cornwallis of Eye, owns Broome Hall, a palace of the fourteenth century.

"The most noble Algernon Capel, Viscount Maiden, Earl of Essex, has Cashiobury in Hertfordshire, a seat which has the shape of a capital H. and which rejoices sportsmen with its abundance of game.

"Charles, Lord Ossulston, owns Darnley in Middlesex, approached by Italian gardens.

"James Cecil, Earl of Salisbury, has, seven leagues from London, Hatfield House, with its four lordly pavilions, its belfry in the centre, and its grand courtyard of black and white slabs, like that of St. Germain. This palace, which has a frontage two hundred seventy-two feet in length, was built in the reign of James I by the Lord High Treasurer of England, the great-grandfather of the present earl. To be seen there is the bed of one of the Countesses of Salisbury; it is of inestimable value and made entirely of Brazilian wood, which is a panacea against the bites of serpents, and which is called milhombres--that is to say, a thousand men. On this bed is inscribed, Honi soit qui mal y pense.

"Edward Rich, Earl of Warwick and Holland, is owner of Warwick Castle, where whole oaks are burned in the fireplaces.

"In the parish of Sevenoaks, Charles Sackville, Baron Buckhurst, Baron Cranfield, Earl of Dorset and Middlesex, is owner of Knowle, which is as large as a town and is composed of three palaces standing parallel one behind the other, like ranks of infantry. There are six covered flights of steps on the principal frontage, and a gate under a keep with four towers.

"Thomas Thynne, Baron Thynne of Warminster, and Viscount Weymouth, possesses Longleat, in which there are as many chimneys, cupolas, pinnacles, pepper-boxes, pavilions, and turrets, as at Chambord, in France, which belongs to the king.

"Henry Howard, Earl of Suffolk, owns, twelve leagues from London, the palace of Audley End in Essex, which in grandeur and dignity scarcely yi

elds the palm to the Escorial of the King of Spain.

"In Bedfordshire, Wrest House and Park, which is a whole district, inclosed by ditches, walls, woodlands, rivers, and hills, belongs to Henry, Marquis of Kent.

"Hampton Court, in Herefordshire, with its strong embattled keep, and its gardens bounded by a piece of water which divides them from the forest, belongs to Thomas, Lord Coningsby.

"Grimsthorp, in Lincolnshire, with its long façade intersected by turrets in pale, its park, its fish-ponds, its pheasantries, its sheepfolds, its lawns, its grounds planted with rows of trees, its groves, its walks, its shrubberies, its flower-beds and borders, formed in square and lozenge-shape, and resembling great carpets; its race-courses, and the majestic sweep for carnages to turn in at the entrance of the house--belongs to Robert, Earl Lindsey, hereditary lord of the forest of Waltham.

Les Miserables

Les Miserables The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame The Man Who Laughs

The Man Who Laughs The Last Day of a Condemned Man

The Last Day of a Condemned Man The Toilers of the Sea

The Toilers of the Sea Waterloo

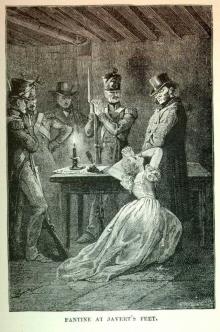

Waterloo Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine

Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius

Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette

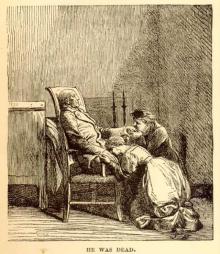

Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean

Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)