- Home

- Victor Hugo

The Toilers of the Sea Page 4

The Toilers of the Sea Read online

Page 4

X

HISTORY, LEGEND, RELIGION

The original six parishes of Guernsey belonged to a single seigneur, Neel, viscount of Cotentin, who was defeated in the Battle of the Dunes in 1047. At that time, according to Dumaresq, there was a volcano in the Channel Islands. The date of the twelve parishes of Jersey is inscribed in the Black Book of Coutances Cathedral. The seigneur of Briquebec had the style of baron of Guernsey. Alderney was a fief held by Henri l'Artisan. Jersey was ruled by two thieves, Caesar and Rollo.20 Haro 21 is an appeal to the duke ("Ha! Rollo!"); or perhaps it comes from the Saxon haran, to cry. The cry haro was repeated three times, kneeling on the highway, and all work ceased in the area until justice had been done. Before Rollo, duke of the Normans, the archipelago had been ruled by Solomon, king of the Bretons. As a result there is much of Normandy in Jersey and much of Brittany in Guernsey. On these islands nature reflects history: Jersey has more meadowland, Guernsey more rocks; Jersey is greener, Guernsey harsher. The islands were covered with noble mansions. The earl of Essex left a ruin on Alderney, Essex Castle. Jersey has Mont Orgueil; Guernsey has Castle Cornet. Castle Cornet stands on a rock that was once a holm, that is, a helmet. The same metaphor is found in the Casquets (casques = helmets). Castle Cornet was besieged by the Picard pirate Eustache, Mont Orgueil by Du Guesclin22; fortresses, like women, boast of their besiegers when they are illustrious. In the fifteenth century a pope declared Jersey and Guernsey neutral. He was thinking of war, not of schism. Calvinism, preached on Jersey by Pierre Morice and on Guernsey by Nicolas Baudouin, arrived in the Norman archipelago in 1563. Calvin's doctrines have prospered there, as have Luther's, though nowadays much troubled by Wesleyanism, an offshoot of Protestantism that now contains the future of England. Churches abound in the archipelago. It is worth considering them in detail. Everywhere there are Protestant churches; Catholicism has been left behind. Any given area on Jersey or Guernsey has more chapels than any area of the same size in Spain or Italy. Methodists proper, Primitive Methodists, other Methodist sects, Independent Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Millenarians, Quakers, Bible Christians, Plymouth Brethren, Non-Sectarians, etc.; add also the episcopal Anglican church and the papist Roman church. On Jersey there is a Mormon chapel.

In St. George's Fountain, at Le Catel, girls see the image of their future husband. Another spring, in St. Andrew's, I think, compels liars who have been unfortunate enough to drink from it to tell the truth. If a woman scrapes a stone in a dolmen, mixes the resultant powder, known as perelle, into water, and drinks it, she is sure to have sturdy children. The wall of a church can be scraped with similar success. In every bay there lives an elf who, if a child gives him a cake, will in due course, according to sex, give the little girl a dowry when she reaches marriageable age and the boy, when he becomes a man, a fully rigged boat. There are two giants: the giant Longis, father of Gayoffe, father of Bolivorax, father of Pantagruel,23 and the giant Bodu, who has now been transformed into a black dog, having been punished by the fairies for his dalliance with a princess. This black dog, Bodu, competes in old wives' tales with a white dog, who is Gaultier de la Salle, the bailiff who was hanged. Connoisseurs of phantoms have all sorts of varieties to study in the Channel Islands: drees are not the same as alleurs; alleurs are not the same as auxcriniers; auxcriniers are not the same as cucuches. In these parts anyone encountering a black hen at nightfall feels some apprehension.

In certain parishes there has been something of a return to Catholicism. At present crosses are beginning to grow on the tips of church spires. It is a sign of Puseyism.24 The organ is now heard in churches, and even in chapels, which would have aroused John Knox's indignation. Saintly persons now abound; some of them possess to a very remarkable degree a horror of "miscreants." In many people this horror seems innate. Protestantism excels, no less than Catholicism, in promoting it. A woman of the highest society in London is famous for her ability to faint in houses where there is a copy of Dr. Colenso's book.25 She enters a house and cries: "The book is here!" and then swoons. A search is carried out and the book is found. This is a very valuable kind of faculty.

Orthodox Bibles are distinguished by their spelling of Satan without a capital, "satan." They are quite right.

Speaking of Satan, they hate Voltaire. The word Voltaire, it seems, is one of the pronunciations of the name of Satan. When it is a question of Voltaire all dissidences are forgotten; Mormon and Anglican views coincide; there is general agreement in anger; and all sects are united in hatred. The anathema directed against Voltaire is the point of intersection of all varieties of Protestantism. It is a remarkable fact that Catholicism detests Voltaire and Protestantism execrates him. Geneva outbids Rome. There is a crescendo in malediction. Calas, Sirven, and so many eloquent pages against the dragonnades count for nothing.26

Voltaire denied a dogma: that is enough. He defended Protestants but he wounded Protestantism; and the Protestants pursue him with a very orthodox ingratitude. A man who had occasion to speak in public in St. Helier to gain support for a good cause was warned that if he mentioned Voltaire in his speech27 the collection would be a failure. So long as the past has breath enough to make itself heard, Voltaire will be rejected. Listen to all these voices: he has neither genius nor talent nor wit. In his old age he was insulted; after his death he is proscribed. He is eternally "discussed": in this his glory consists. Is it possible to speak of Voltaire calmly and with justice? When a man dominates an age and incarnates progress, he cannot expect criticism: only hatred.

XI

OLD HAUNTS AND OLD SAINTS

The Cyclades form a circle; the archipelago of the Channel forms a triangle. When you look at a map, which is a bird's-eye view for man, the Channel Islands, a triangular segment of sea, are bounded by three culminating points: Alderney to the north, Guernsey to the west, and Jersey to the south. Each of these three mother islands has around it what might be called its chickens, a series of islets. Alderney has Burhou, Ortach, and the Casquets; Guernsey has Herm, Jethou, and Lihou; Jersey has on the side facing France the semicircle of St. Aubin's Bay, toward which the two groups, scattered but distinct, of the Grelets and the Minquiers seem to be hastening, like two swarms of bees heading for the doorway of the hive, in the blue of the water, which, like the sky, is azure. In the center of the archipelago is Sark, with its associated Brecqhou and Goat Island, which provides a link between Guernsey and Jersey. The comparison between the Cyclades and the Channel Islands would certainly have struck the mystical and mythical school that, under the Restoration, was centered on de Maistre by way of d'Eckstein28 and would have served it as a symbol: the rounded archipelago of Hellas (ore rotundo, harmonious in style), the archipelago of the Channel sharp, bristling, aggressive, angular; the one in the image of harmony, the other of dispute. It is not for nothing that one is Greek and the other Norman.

Once, in prehistoric times, these islands in the Channel were wild. The first islanders were probably some of those primitive men of whom specimens were found at Moulin-Quignon,29 who belonged to the race with receding jaws. For half the year they lived on fish and shellfish, for the other half on what they could pick up from wrecks. Pillaging their coasts was their main resource. They recognized only two seasons in the year, the fishing season and the shipwreck season, just as the Greenlanders call summer the "reindeer hunt" and winter the "seal hunt." All these islands, which later became Norman, were expanses of thistles and brambles, wild beasts' dens and pirates' lairs. An old local chronicler refers, energetically, to "rat traps" and "pirate traps." The Romans came, and probably brought about only a moderate advance toward probity: they crucified the pirates and celebrated the Furrinalia, the rogues' festival. This festival is still celebrated in some of our villages on July 25 and in our towns throughout the year.

Jersey, Sark, and Guernsey were formerly called Ange, Sarge, and Bissarge; Alderney is Redana, or perhaps Thanet. There is a legend that on Rat Island, insula rattorum, the promiscuity of male rabbits a

nd female rats gave rise to the guinea pig.

According to Furetiere,30 abbot of Chalivoy, who reproached La Fontaine with being ignorant of the difference between bois en grume (hewn timber with its bark on) and bois marmenteau (ornamental timber), it was a long time before France noticed the existence of Alderney off its coasts. And indeed Alderney plays only an imperceptible part in the history of Normandy. Rabelais, however, knew the Norman archipelago; he names Herm and Sark, which he calls Cercq. "I assure you that this land is the same that I have formerly seen, the islands of Cercq and Herm, between Brittany and England" (edition of 1558, Lyons, p. 423).

The Casquets are a redoubtable place for shipwrecks. Two hundred years ago the English ran a trade in the fishing up of cannon there. One of these cannon, covered with oysters and mussels, is now in the museum in Valognes.31 Herm is an eremos.32 Saint Tugdual, a friend of Saint Sampson, prayed on Herm, just as Saint Magloire (Maglorius) prayed on Sark. There were hermits' haloes on all these rocky points. Helier prayed on Jersey and Marculf amid the rocks of Calvados. This was the time when the hermit Eparchius was becoming Saint Cybard in the caverns of Angouleme and when the anchorite Crescentius, in the depths of the forests around Trier, caused a temple of Diana to fall down by staring fixedly at it for five years. It was on Sark, which was his sanctuary, his ionad naomh, that Magloire composed the hymn for All Saints, later rewritten by Santeuil, Coelo quos eadem gloria consecrat. It was from there, too, that he threw stones at the Saxons, whose raiding fleets twice disturbed his prayers. The archipelago was also somewhat troubled at this period by the amwarydour, the chieftain of the Celtic settlement. From time to time Magloire crossed the water to consult with the mactierne (vassal prince) of Guernsey, Nivou, who was a prophet. One day Magloire, after performing a miracle, made a vow never to eat fish again. In addition, in order to promote good behavior among the dogs and preserve the monks from guilty thoughts, he banished bitches from the island of Sark--a law that still subsists. Saint Magloire performed other services for the archipelago. He went to Jersey to bring to their senses the people of the island, who had the bad habit on Christmas Day of changing themselves into all kinds of animals in honor of Mithras. Saint Magloire put an end to this misbehavior. In the reign of Nominoe, a feudatory of Charles the Bold, his relics were stolen by the monks of Lehon-les-Dinan. All these facts are proved by the Bollandists, the "Acta Sancti Marculphi," etc., and Abbe Trigan's "Ecclesiastical History." Victricius of Rouen, a friend of Martin of Tours, had his cave on Sark, which in the eleventh century was a dependency of the abbey of Montebourg. Nowadays Sark is a fief immobilized between forty tenants.

XII

RANDOM MEMORIES

In the Middle Ages poor people and poor money went together. One created the other. The poor improvised the sou. Rags and farthings were brothers: so much so that the former sometimes invented the latter. It was a bizarre kind of right, tacitly permitted. There are still traces of this on Guernsey. A quarter of a century ago anyone who had need of a double33 tore a copper button off his jacket; the buttons from soldiers' uniforms were current coin; a scrap metal merchant would cut out pennies from an old cauldron. This coinage circulated freely.

The first steamship to be seen on Guernsey, on its way to somewhere else, gave the idea of having one on the island. It was called the Medina and had a burden of around a hundred tons. It called in at St. Peter Port on June 10, 1823. A regular service of steamers to and from England, by Southampton and Portsmouth, started only much later. The service was run by two small steamships, the Ariadne and the Beresford. Viscount Beresford was then governor of the islands.

Isolation has a long memory, and an island is a form of isolation. Hence the tenacity of memory in islanders. Traditions continue interminably. It is impossible to break a thread stretching backward through the night as far as the eye can reach. People remember everything--a boat that passed that way, a shower of hail, a fish they caught, and, still more understandably, their forebears. Islands are much given to genealogies.

A word in passing about genealogies. We shall have more to say about them. Family trees are venerated in the archipelago. They are much regarded even for cows--more usefully, perhaps, than for people. A countryman will refer to "my ancestors."

When Monsieur Pasquier was made a duke, Monsieur Royer-Collard 34 said to him: "It won't do you any harm." It is the same with genealogies: they do no harm to anyone.

Tattooing is the earliest form of heraldry. The innocence of the savage points toward the pride of nobility. And the Channel Islands are innocent, very innocent, and savage, to a certain degree. In these sea-borne territories, where a kind of saltiness preserves everything, even vanities, people have a firm faith in their own antiquity. In a way this is respectable and touching. It leads to impressive claims. If these claims are made in the presence of a skeptical Frenchman he smiles; if he is polite as well as skeptical he bows. One day (May 26, 1865) I had two visitors, a Jersey man and an Englishman, both perfect gentlemen. The Jersey man said: "My name is Larbalestier." Seeing that this did not sufficiently impress me, he added: "I am a Larbalestier, of a family that went on the Crusades." The Englishman said: "My name is Brunswill. I am descended from William the Conqueror." I asked them: "Do you know a Guernsey man, Mr. Overend, who is descended from Rollo?"

There is a Granite Club in St. Sampson. Its members are stone breakers, who wear a blue rosette in their buttonhole on May 31. May is also the cricket season.

The Channel Islands are remarkable for their impassiveness. A matter that stirs passions in England seems to pass unnoticed here. The author of this book happened one day to commit a barbarism in the English language, which he did all the more readily because he knows no English. Deceived by false information given by a misprint in a pocket dictionary, he wrote "bugpipe" instead of "bagpipe." A u instead of an a! It was an enormity. "Bug" and not "bag": it was almost as bad as "shibboleth" instead of "sibboleth." Once upon a time England burned people at the stake for that. This time Albion contented itself with raising its hands to heaven. How can a man who knows no English make a mistake in English? The newspapers made this scandal headline news. Bugpipe! There was a kind of uprising throughout Great Britain; but, strange to say, Guernsey remained calm.35

Two varieties of traditional French farmhouse are to be seen on Guernsey. On the east side it is the Norman type, on the west side the Breton. The Norman farm has more architecture, the Breton farm more trees. The Norman farm stores its crops in a barn; the Breton farm, more primitive, shelters its crops under a thatched roof borne on rugged columns that are almost cyclopean in aspect--shapeless cylinders of undressed stones bonded with Portland cement. From these farms women, some still wearing the old Guernsey headdress, set out for the town with their baskets of vegetables and fruit on a queriot, a donkey cart. When a market woman earns her first money of the day she spits on it before putting it in her pocket. Evidently this brings luck.

These good countryfolk of the islands have all the old prickliness of the Normans. It is difficult to strike the right note in dealing with them. Walking out one winter day when it was raining, an acquaintance of ours noticed an old woman in rags, almost barefoot. He went up to her and slipped a coin in her hand. She turned around proudly, dropped the money to the ground, and said: "What do you take me for? I am not poor. I keep a servant." If you make the opposite mistake you are no better received. A countryman takes such politeness as an offense. The same acquaintance once addressed a countryman, asking: "Are you not Mess Leburay?" The man frowned, saying: "I am Pierre Leburay. I am not entitled to be called Mess."36

Ivy abounds, clothing rocks and house walls with magnificence. It clings to any dead branch and covers it completely, so that there are never any dead trees; the ivy takes the trunk and branches of a tree and puts leaves on them. Bales of hay are unknown: instead you will see in the fields mounds of fodder as tall as houses. These are cut up like a loaf of bread, and you will be brought a lump of hay to meet the needs of

your cowshed or stable. Here and there, even quite far inland, amid fruit and apple orchards, you will see the carcasses of fishing boats under construction. The fisherman tills his fields, the farmer is also a fisherman: the same man is a peasant of the land and a peasant of the sea.

In certain types of fishery the fisherman drops his net into the sea and anchors it on the bottom, with cork floats supporting it on the surface, and leaves it. If a ship passes that way during the night it cuts the net, which drifts away and is lost. This is a heavy loss, for a net may cost as much as two or three thousand francs. Mackerel are caught in a net with meshes too wide for their head and too small for their body; the fish, unable to move forward, try to back out and are caught by the gills. Mullet are caught with the trammel, a French type of net with triple meshes, which work together to trap the fish. Sand eels are caught with a hoop net, half meshed and half solid, which acts as both a net and a bag.

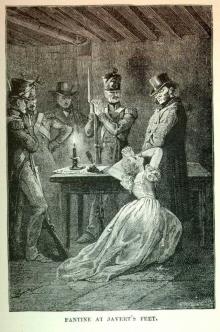

Les Miserables

Les Miserables The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame The Man Who Laughs

The Man Who Laughs The Last Day of a Condemned Man

The Last Day of a Condemned Man The Toilers of the Sea

The Toilers of the Sea Waterloo

Waterloo Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine

Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius

Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette

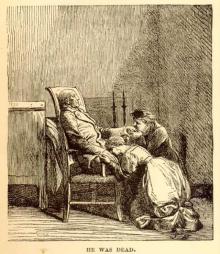

Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean

Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)