- Home

- Victor Hugo

Told Under Canvas Page 5

Told Under Canvas Read online

Page 5

Whilst the old soldier thus explained to me his views—a little narrow-minded perhaps, but full of the frankness of conviction—the stormy argument was at its height. A certain planter, one amongst the few who were bitten with the rabid mania of the revolution, and who called himself Citizen General C——, because he had assisted at a few sanguinary executions, exclaimed—

“We must have punishments rather than battles. Every nation must exist by terrible examples; let us terrify the negroes. It was I who quieted the slaves during the risings of June and July by lining the approach to my house with a double row of negro heads. Let each one join me in this, and let us defend the entrances to Cap with the slaves who are still in our hands.”

“How?” “What do you mean?” “Folly,” “The height of imprudence,” was heard on all sides.

“You do not understand me, gentlemen. Let us make a ring of negro heads, from Fort Picolet to Point Caracole. The rebels, their comrades, will not then dare to approach us. I have five hundred slaves who have remained faithful—I offer them at once.”

This abominable proposal was received with a cry of horror.

“It is infamous! It is too disgusting!” was repeated by at least a dozen voices.

“Extreme steps of this sort have brought us to the verge of destruction,” said a planter. “If the execution of the insurgents of June and July had not been so hurried on, we should have held in our hands the clue to the conspiracy, which the axe of the executioner divided for ever.”

Citizen C—— was silenced for a moment by this outburst; then in an injured tone he muttered—

“I did not think that I, above all others, should have been suspected of cruelty. Why, all my life I have been mixed up with the lovers of the negro race. I am in correspondence with Briscot and Pruneau de Pomme-Gouge, in France; with Hans Sloane, in England; with Magaw, in America; with Pezll, in Germany; with Olivarius, in Denmark; with Wadstiörn, in Sweden; with Peter Paulus, in Holland; with Avendaño, in Spain; and with the Abbé Pierre Tamburini, in Italy!”

His voice rose as he ran through the names of his correspondents amongst the lovers of the African race, and he terminated his speech with the contemptuous remark—

“But, after all, there are no true philosophers here.”

For the third time M. de Blanchelande asked if any one had anything further to propose.

“Your Excellency,” cried one, “let us embark on board the Leopard, which lies at anchor off the quay.”

“Let us put a price on the head of Bouckmann,” exclaimed another.

“Send a report of what has taken place to the Governor of Jamaica,” suggested a third.

“A good idea, so that he may again send us the ironical help of five hundred muskets!” sneered a member of the Provincial Assembly. “Your Excellency, let us send the news to France, and wait for a reply.”

“Wait—a likely thing indeed,” exclaimed M. de Rouvray; “and do you think that the blacks will wait, eh? And the flames that encircle our town, do you think that they will wait? Your Excellency, let the tocsin be sounded, and send dragoons and grenadiers in search of the main body of the rebels. Form a camp in the eastern division of the island; plant military posts at Trou and at Vallieres. I will take charge of the plain of Dauphin; but let us lose no more time, for the moment for action has arrived.”

The bold and energetic speech of the veteran soldier hushed all differences of opinion. The general had acted wisely. That secret knowledge which every one possesses most conducive to his own interests, caused all to support the proposal of General de Rouvray; and whilst the Governor with a warm clasp of the hand showed his old friend that his counsels had been appreciated, though they had been given in rather a dictatorial manner, the colonists urged for the immediate carrying out of the proposals.

I seized the opportunity to obtain from M. de Blanchelande the permission that I so ardently desired, and, leaving the room, mustered my company in order to return to Acul—though, with the exception of myself, all were worn out with the fatigue of their late march.

CHAPTER XIV.

Day began to break as I entered the market-place of the town, and began to rouse up the soldiers, who were lying about in all directions wrapped in their cloaks, and mingled pell-mell with the Red and Yellow Dragoons, fugitives from the country, cattle bellowing, and property of every description sent in for security by the planters. In the midst of all this confusion I began to pick out my men, when I saw a private in the Yellow Dragoons, covered with dust and perspiration, ride up at full speed. I hastened to meet him, and in a few broken words he informed me that my fears were realized—that the insurrection had spread to Acul, and that the negroes were besieging Fort Galifet, in which the planters and the militia had taken refuge. I must tell you that this fort was by no means a strong one, for in St. Domingo they dignify the slightest earthwork with the name of fort.

There was not a moment to be lost. I mounted as many of my soldiers as I could procure horses for, and taking the dragoon as a guide, I reached my uncle’s plantation about ten o’clock. I scarcely cast a glance at the enormous estate, which was nothing but a sea of flame, over which hovered huge clouds of smoke, through which every now and then the wind bore trunks of trees covered with sparks. A terrible rustling and crackling sound seemed to reply to the distant yells of the negroes which we now began to hear, though we could not as yet see them. The destruction of all this wealth, which would eventually have become mine, did not cause me a moment’s regret. All I thought of was the safety of Marie—what mattered anything else in the world to me? I knew that she had taken refuge in the fort, and I prayed to God that I might arrive in time to rescue her. This hope sustained me through all the anxiety I felt, and gave me the strength and courage of a lion. At length a turn in the road permitted us to see the fort. The tricolour yet floated on its walls, and a well-sustained fire was kept up by the garrison. I uttered a shout of joy. “Gallop, spur on!” said I to my men, and redoubling our pace we dashed across the fields in the direction of the scene of action.

Near the fort I could see my uncle’s house; the doors and windows were dashed in, but the walls still stood, and shone red with the reflected glare of the flames, which, owing to the wind being in a contrary direction, had not yet reached the building.

A crowd of the insurgents had taken possession of the house, and showed themselves at the windows and on the roof. I could see the glare of torches and the gleam of pikes and axes, whilst a brisk fire of musketry was kept up on the fort.

Another strong body of negroes had placed ladders against the walls of the fort and strove to take it by assault, though many fell under the well-directed fire of the defenders.

These black men always returning to the charge after each repulse, looked like a swarm of ants endeavouring to scale the shell of a tortoise, and shaken off by each movement of the sluggish reptile.

We reached the outworks of the fort, our eyes fixed upon the banner which still floated above it. I called upon my men to remember that their wives and children were shut up within those walls, and I urged them to fly to their rescue. A general cheer was the reply, and, forming column, I was on the point of giving the order to charge, when a loud yell was heard, a cloud of smoke enveloped the fort, and for a time concealed it from our sight; a roar was heard like that of a furnace in full blast, and as it cleared away we saw a red flag floating proudly above the dismantled walls. All was over. Fort Galifet was in the hands of the insurgents.

CHAPTER XV.

I cannot tell you what my feelings were at this terrible spectacle. The fort was taken, its defenders slain, and twenty families massacred; but I confess, to my shame, that I thought not of this. Marie was lost to me—lost, after having been made mine but a few brief hours before. Lost, perhaps, through my fault, for had I not obeyed the orders of my uncle in going to Cap I should have been by her side to defend her, or at least to die with her. These thoughts raised my grief t

o madness, for my despair was born of remorse.

However, my men were maddened at the sight. With a shout of “Revenge,” with sabres between their teeth and pistols in either hand, they burst into the ranks of the victorious insurgents. Although far superior in numbers the negroes fled at their approach; but we could see them on our right and left, before and behind us, slaughtering the colonists, and casting fuel on the flames. Our rage was increased by their cowardly conduct.

Thaddeus, covered with wounds, made his escape through a postern gate. “Captain,” said he, “your Pierrot is a sorcerer, an obi as these infernal negroes call him—a devil, I say. We were holding our position, you were coming up fast; all seemed saved—when by some means, which I do not know, he penetrated into the fort, and there was an end of us. As for your uncle and Madam——”

“Marie,” interrupted I, “where is Marie?”

At this instant a tall black burst through a blazing fence, carrying in his arms a young woman who shrieked and struggled: it was Marie, and the negro was Pierrot!

“Traitor,” cried I.

I fired my pistol at him; one of the rebels threw himself in the way, and fell dead. Pierrot turned, and addressed a few words to me which I did not catch; and then grasping his prey tighter, dashed into a mass of burning sugar-canes. A moment afterwards a huge dog passed me, carrying in his mouth a cradle in which lay my uncle’s youngest child. Transported with rage, I fired my second pistol at him; but it missed fire. Like a madman I followed on their tracks; but my night march, the hours that I had spent without taking rest or food, my fears for Marie, and the sudden fall from the height of happiness to the depth of misery, had worn me out. After a few steps I staggered, a cloud seemed to come over me, and I fell senseless.

CHAPTER XVI.

When I recovered my senses I found myself in my uncle’s ruined house, supported in the arms of my faithful Thaddeus, who gazed upon me with an expression of the deepest anxiety. “Victory!” exclaimed he, as he felt my pulse begin to beat. “Victory! the negroes are in full retreat and my captain has come to life again.”

I interrupted his exclamations of joy by putting the only question in which I had any interest.

“Where is Marie?”

I had not yet collected my scattered ideas: I felt my misfortune, without the recollection of it. At my question Thaddeus hung his head.

Then my memory returned to me, and, like a hideous dream, I recalled once more the terrible nuptial day, and the tall negro bearing away Marie through the flames.

The flame of rebellion which had broken out in the colony caused the whites to look on the blacks as their mortal enemies, and made me see in Pierrot, the good, the generous, and the devoted, who owed his life three times to me, a monster of ingratitude and a rival.

The carrying off of my wife on the very night of our nuptials proved too plainly to me, what I had at first only suspected, and I now knew that the singer of the wood was the wretch who had torn my wife from me. In a few hours how great a change had taken place.

Thaddeus told me that he had vainly pursued Pierrot and his dog when the negroes, in spite of their numbers, retired, and that the destruction of my uncle’s property still continued, without the possibility of its being arrested.

I asked what had become of my uncle. He took my hand in silence and led me to a bed, the curtains of which he drew.

My unhappy uncle was there, stretched upon his blood-stained couch, with a dagger driven deeply into his heart. By the tranquil expression of his face it was easy to see that the blow had been struck during his sleep.

The bed of the dwarf Habibrah, who always slept at the foot of his master’s couch, was also profusely stained with gore, and the same crimson traces could be seen upon the laced coat of the poor fool, cast upon the floor a few paces from the bed.

I did not hesitate for a moment in believing that the dwarf had died a victim to his affection for my uncle, and that he had been murdered by his comrades, perhaps in the effort to defend his master. I reproached myself bitterly for the prejudice which had caused me to form so erroneous an estimate of the characters of Pierrot and Habibrah; and of the tears I shed at the tragic fate of my uncle, some were dedicated to the end of the faithful fool.

By my orders his body was carefully searched for, but all in vain, and I imagined that the negroes had cast the body into the flames; and I gave instructions that, in the funeral service over my uncle’s remains, prayers should be said for the repose of the soul of the devoted Habibrah.

CHAPTER XVII.

Fort Galifet had been destroyed, our house was in ruins; it was useless to linger there any longer, so that evening I returned to Cap. On my arrival there I was seized with a severe fever. The effort that I had made to overcome my despair had been too violent; the spring had been bent too far and had snapped. Delirium came on. My broken hopes, my profound love, my lost future, and, above all, the torments of jealousy, made my brain reel.

It seemed as if fire flowed in my veins; my head seemed ready to burst, and my bosom was filled with rage. I pictured to myself Marie in the arms of another lover, subject to the power of a master, of a slave, of Pierrot! They told me afterwards that I sprang from my bed, and that it took six men to prevent me from dashing out my brains against the wall. Why did I not die then?

The crisis, however, passed. The doctors, the care and attention of Thaddeus, and the latent powers of youth, conquered the malady; would that it had not done so. At the end of ten days I was sufficiently recovered to lay aside grief, and to live for vengeance.

Hardly arrived at a state of convalescence, I went to M. de Blanchelande, and asked for employment. At first he wished to give me the command of some fortified post, but I begged him to attach me to one of the flying columns, which from time to time were sent out to sweep those districts in which the insurgents had congregated. Cap had been hastily put in a position of defence, for the revolt had made terrible progress, and the negroes of Port au Prince had begun to show symptoms of disaffection. Biassou was in command of the insurgents at Lumbé, Dondon, and Acul; Jean François had proclaimed himself generalissimo of the rebels of Maribarou, and Bouckmann, whose tragic fate afterwards gave him a certain celebrity, with his brigands ravaged the plains of Limonade; and lastly, the bands of Morne-Rouge had elected for their chief a negro called Bug-Jargal.

If report was to be believed, the disposition of this man contrasted very favourably with the ferocity of the other chiefs. Whilst Bouckmann and Biassou invented a thousand different methods of death for such prisoners as fell into their hands, Bug-Jargal was always ready to supply them with the means of quitting the island. M. Colas de Marjue, and eight other distinguished colonists, were by his orders released from the terrible death of the wheel to which Bouckmann had condemned them, and many other instances of his humanity were cited, which I have not time to repeat.

My hoped for vengeance, however, still appeared to be far removed. I could hear nothing of Pierrot. The insurgents commanded by Biassou continued to give us trouble at Cap; they had once even endeavoured to take position on a hill that commanded the town, and had only been dislodged by the battery from the citadel being directed upon them.

The Governor had therefore determined to drive them into the interior of the island. The militia of Acul, of Lumbé, of Ouanaminte, and of Maribarou, joined with the regiment of Cap, and the Red and Yellow Dragoons, formed one army of attack; whilst the corps of volunteers under the command of the merchant Poncignon, with the militia of Dondon and Quartier-Dauphin, composed the garrison of the town.

The Governor desired first to free himself from Bug-Jargal, whose incursions kept the garrison constantly on the alert, and he sent against him the militia of Ouanaminte, and a battalion of the regiment of Cap. Two days afterwards the expedition returned, having sustained a severe defeat at the hands of Bug-Jargal. The Governor, however, determined to persevere, and a fresh column was sent out with fifty of the Yellow Drago

ons and four hundred of the militia of Maribarou. This second expedition met with even less success than the first. Thaddeus, who had taken part in it, was in a violent fury, and upon his return vowed vengeance against the rebel chief Bug-Jargal.

A tear glistened in the eyes of D’Auverney; he crossed his arms on his breast, and appeared to be for a few moments plunged in a melancholy reverie. At length he continued.

CHAPTER XVIII.

The news had reached us that Bug-Jargal had left Morne-Rouge, and was moving through the mountains to effect a junction with the troops of Biassou. The Governor could not conceal his delight. “We have them,” cried he, rubbing his hands. “They are in our power.”

By the next morning the colonial forces had marched some four miles to the front of Cap. At our approach the insurgents hastily retired from the positions which they had occupied at Port-Mayat and Fort Galifet, and in which they had planted siege guns which they had captured in one of the batteries on the coast. The Governor was triumphant, and by his orders we continued our advance. As we passed through the arid plains and the ruined plantations, many a one cast an eager glance in search of the spot which was once his home, but in too many cases the foot of the destroyer had left no traces behind. Sometimes our march was interrupted by the conflagration having spread from the lands under cultivation, to the virgin forests.

In these regions, where the land is untilled and the vegetation abundant, the burning of a forest is accompanied with many strange phenomena. Far off, long before the eye can catch the cause, a sound is heard like the rush of a cataract over opposing rocks, the trunks of the trees flame out with a sudden crash, the branches crackle, and the roots beneath the soil all contribute to the extraordinary uproar. The lakes and the marshes in the interior of the forests boil with the heat. The hoarse roar of the coming flame stills the air, causing a dull sound, sometimes increasing and sometimes diminishing in intensity as the conflagration sweeps on or recedes. Occasionally a glimpse can be caught of a clump of trees surrounded by a belt of fire, but as yet untouched by the flames; then a narrow streak of fire curls round the stems, and in another instant the whole becomes one mass of gold-coloured fire; then up rises the column of smoke driven here and there by the breeze. It takes a thousand fantastic forms, spreads itself out, diminishes in an instant; at one moment it is gone, in another it returns with greater density; then all becomes a thick black cloud, with a fringe of sparks, a terrible sound is heard, the sparks disappear, and the smoke ascends, disappearing at last in a mass of red ashes, which sink down slowly upon the blackened ground.

Les Miserables

Les Miserables The Hunchback of Notre-Dame

The Hunchback of Notre-Dame The Man Who Laughs

The Man Who Laughs The Last Day of a Condemned Man

The Last Day of a Condemned Man The Toilers of the Sea

The Toilers of the Sea Waterloo

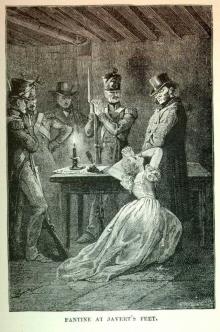

Waterloo Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine

Les Misérables, v. 1/5: Fantine Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius

Les Misérables, v. 3/5: Marius Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette

Les Misérables, v. 2/5: Cosette Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean

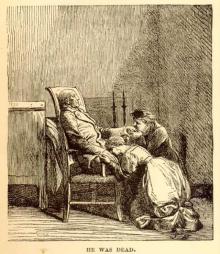

Les Misérables, v. 5/5: Jean Valjean Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Hunchback of Notre Dame (Barnes & Noble Classics Series) Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)

Les Miserables (abridged) (Barnes & Noble Classics Series)